Review

by Andrew Osmond,The Many Worlds of Takahata Isao

Book Review

| Synopsis: |  |

||

At last, Anglophone readers have an in-depth academic study of the director Isao Takahata, who's most famous for his films at Studio Ghibli but whose work goes far beyond that. Edited by Lindsay Coleman, Rayna Denison, and David Desser, the book explores the depth and breadth of Takahata's body of work. |

|||

| Review: | |||

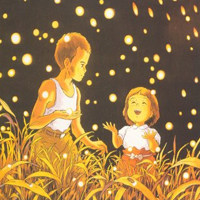

This is the first English-language book-length academic study of Isao Takahata, spanning nearly fifty years of his work, from Horus, Prince of the Sun in 1968 to The Tale of the Princess Kaguya in 2013. It's an anthology, with most of the writers taking one title each and examining it from historical, political, and aesthetic angles. Some of these authors will be familiar if you've dipped into anime studies, including Jonathan Clements and Helen McCarthy, authors of The Anime Encyclopedia, Susan Napier, author of Miyazakiworld, Thomas Lamarre, author of The Anime Machine and Rayna Denison, author of Anime: A Critical Introduction. As you may guess from the title, the book adopts the style of putting Japanese family names first, so get used to that. As of writing, the hardback copy of the book is available for a hefty US$55, though the Kindle copy is a more affordable US$28. That's moderate by the standard of academic studies, though a library loan is also an option. It's an uneven book, where some chapters are far more heavy-going than others, and often not to their benefit. It's also clear that the writers don't all agree with one another – perhaps the book could have benefited from a roundtable discussion to explore their differences. Some chapters are far better than others. Overall, I found the book edifying as a way to remind myself of the breadth of Takahata's work and the complex issues they raise.  ©1988 Akiyuki Nosaka/Shinchosha Co. That's a lot of ground covered, though; even so, the book leaves out some important titles. There's almost nothing on Takahata's 1976 series Marco - From the Apennines to the Andes or his 1979 Anne of Green Gables; the latter was remade as 2025's Anne Shirley. Of course, it's sensible for the book to lean towards Takahata's anime that can be seen in Anglophone territories. It's sad, though, that so much of the director's work still isn't accessible in English. (You can see Takahata's Anne on an official YouTube stream, but it's dub-only.)  © Etsumi Haruki / FutabashaTMS Clements explains Chie's debts to “manzai” comedy double-acts in Japan and how by the time the film opened, the bratty Chie's actress was an elected politician! We also learn how painstakingly Takahata recreated the source Chie manga, down to particular character poses. As the animator Yasuo Ōtsuka, who worked on the film, pointed out, Takahata's fidelity to the source was most unlike a certain other director, the one who turned everything he adapted into “Miyazaki World.”  ©1991 岡本 螢・刀根夕子・Studio Ghibli・NHK Desser also explores the documentary elements of Takahata's film in the farming sequences. However, I think these play more like a propaganda film about the joys of the country that wants you to recognize you're watching didactic propaganda. You may still agree with it, but that's left up to you. As the book's chapter on My Neighbors the Yamadas points up, Takahata studied the theories of Bertolt Brecht; in Takahata's words, art that can “maintain and implement a certain distance between the world described and the spectator.” While Desser doesn't talk much about other anime, his comments remind us that Only Yesterday can be linked to works by other hands. At one point, Desser suggests, “Only Yesterday marked the beginning of adult-oriented anime in that its primary audience would be those who could experience the sense of what I am calling 'tainted nostalgia'” – that is, memories mixed between joyous, ambivalent, and bad. Just a few years after Only Yesterday, we'd get an anime masterpiece of that kind in a different genre, Macross Plus. Desser's discussion of Only Yesterday's artful transitions between past and present is very interesting for anyone studying Satoshi Kon. In Only Yesterday, the “past” and “present” scenes are drawn in different styles, with the past shown with softer colors and many white spaces. I agree with Desser that this isn't meant to suggest the past is “fading.” I do think that Takahatata is saying we can enter and interrogate the past in a way we can't do with the present moment.  © 1999 Hisaichi Ishii/Isao Takahata/Studio Ghibli, NHD However, the seeds of these ideas were already visible in Only Yesterday, and I was surprised Montero-Plata doesn't make the link. Still, she gives a great account of how Takahata forced Ghibli to “accommodate the commercial release of a film [Yamadas] that was more connected to independent, experimental animation… [Yamadas] “cast aside Ghibli's production structure, distanced itself from Ghibli's visual style, slowed the company's revenue streams at the Japanese box office, and damaged the training system implemented at Ghibli to shape apprentice artists to Ghibli's methods.” Some readers may find that story more interesting than the Yamadas film. However, Montero-Plata also gives a subtle and sympathetic account of what Takahata set out to do in it, encouraging a kinder, more accepting view of life. Yamadas' outlook is comparable to America's Peanuts, but it's steeped in Japanese culture. After drawing on “manzai” comedy for Chie the Brat, in Yamadas, Takahata draws on "rakugo" storytelling, where minimalism and imagination are paramount. Twelve years before Yamadas' minimal animation, Takahata had ventured into live-action with 1987's The Story of Yanagawa's Canals. Nearly three hours long, the film depicts the efforts to clean up venerable canals in the titular Japanese city, on the southern island of Kyushu. The film is covered by Rayna Denison, who goes through the murky, sometimes contradictory accounts of how Yanagawa got started. It wasn't a Ghibli film, but one story goes that it helped create Ghibli, so that Hayao Miyazaki could make a film to fund Yanagawa! One source Denison seems to have missed, by the way, is a fairly detailed account in The Art of Castle in the Sky, published in English by Viz Media. That pushes the story that the project originated as an anime teen drama film set in Yanagawa, sketched out by Miyazaki after he visited the city, although Takahata was soon nominated as the provisional director. The vague story would have involved a long-buried canal and the secret of a beautiful girl's birth. My own speculation is that Miyazaki might have been influenced by the 1980 shojo manga From Up On Poppy Hill, which he eventually adapted as the writer of its 2011 film version by Ghibli. In her chapter, Denison discusses how Takahata's actual film fits – and sometimes doesn't fit - into Japanese documentary traditions. She also argues that Takahata's stance is pro-environmentalist, “but not necessarily environmentalist in and of itself.” Rather, the director highlights how humans have reshaped the natural landscape, something that's also celebrated in Only Yesterday. If you're looking for links to non-Takahata anime, the obvious starting point is Spirited Away, in which polluted and neglected rivers are a huge part of the story. But there's also Mamoru Oshii's Patlabor: The Movie, made just a couple of years after Yanagawa. Much of that film revolves around modern Tokyo's blithe use of water and the neglected waterways beneath the city. In another chapter, Shiro Yoshioka examines how Takahata rose from an anonymous director to a respected artist. This was partly thanks to Japanese anime fandom and magazines such as Animage, but another turning point was when the publisher Shinchosha energetically marketed Grave of the Fireflies to non-anime fans. Around that time, Takahata himself started making political statements beyond anime, turning himself into a real-world commentator. For instance, he wrote an angry magazine article about how Japan's Self-Defense Force minimized the carnage of the air raids in Japan in World War II. Takahata had experienced such raids himself as a child and showed them in Grave.  © ZUIYO Ashmore rightly notes that Takahata's version makes an important change to the original novel by Johanna Spyri. In the book, Heidi's goatherd friend Peter becomes jealous of Heidi's new friend Clara and smashes her wheelchair, a shocking crime. However, Ashmore claims Peter accidentally breaks the chair in Takahata's version, whereas actually it's Clara who does that herself. Of the other chapters, Susan Napier's account of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is surprisingly lightweight, though I appreciated her notes on the Buddhist iconography in the last cosmic scene. But the book's biggest let-downs are the chapters on Grave of the Fireflies, by Lindsay Coleman, and Pom Poko, by Thomas Lamarre. If you need reminding, Grave is about two Japanese children struggling to survive at the end of World War II. Pom Poko is about canine tanuki trying to fight the humans destroying their homes. Both chapters are expressly politicized readings of the respective films, referring to huge bodies of critical theory outside anime and raising interesting subjects. By and large, though, they're unconvincing as argument or analysis. They often seem blinkered as to what the films are actually doing, insisting instead on what they should be doing in numbing harangues. Discussing Grave, Coleman pushes the Marxist line that a successful anti-war film should give the viewer “a deeper, critical understanding of the systemic defects and capitalist motivation that frequently feed conflicts.” But there's no convincing demonstration of how Grave achieves this, or that it meant to. The actual film highlights the choices of the boy character, Seita, which are presented as his own decisions, even his own fault. Coleman claims, “Seita's actions represent a conflict between traditional Japanese ideals and the demands of a contemporary, war-torn society.” How this conflict leads to a Marxist enlightenment for the viewer is anyone's guess.  ©1994 Isao Takahata/Studio Ghibli, NH But these insights are hidden in a morass of barely argued assertions that quickly spiral out of control. Takahata's tanuki, we are told, are neither animals nor yokai, despite the film presenting them as both. (There are, of course, real tanuki in Japan, natural animals.) When they're shown walking and talking, Lamarre claims, this is not anthropomorphism but 'personation.'” Later, we're told they represent suppressed peoples, though through a flawed prism. It is “important to consider the primordialism and residual colonialism implicit in (Takahata's) articulation of a tanuki people,” Lamarre tuts righteously. Why buy any of this? There are so many other ways to see the tanuki, far more obvious than Lamarre's suggestions. You can see them as anthropomorphized animals, like the rabbits in Watership Down, fighting heroically for survival. Or you can see them as beast-fable figures in an Animal Farm satire of activism going wrong, as the tanuki guerrillas argue over whether to resist humans with violence or non-violence, before breaking down into death cults and suicide squads. Or the tanuki could embody the Japanese imagination, the folklore and yokai art they act out on screen. Of course, there's no need to choose; they're all these things together. If there's one thing that emerges from Takahata's work, it's that there's never one way to utilize tanuki, or fantasy, or animation, or visual art. In his long career, Takahata bent his remarkable energies to create Alpine paradises, Skid Row knockabouts, wartime tragedies, and a moon princess chasing the fleeting essence of life. His work encompasses many worlds indeed. |

|

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of Anime News Network, its employees, owners, or sponsors.

|

| Grade: | |||

Overall : B+

+ An edifying reminder of the breadth and depth of Takahata's work |

|||

| discuss this in the forum | | |||